Nov 20

/

Katarzyna Truszkowska

Beyond Tool Training: A Framework for AI Literacy in Academic Writing

Students are anxious about AI taking their jobs, while educators worry about AI replacing genuine learning. But what is the real problem?

The Question Every Student Is Asking

“We are all worried that artificial intelligence is most likely going to take over our jobs and humanity.” This wasn’t said by a tech journalist or futurist. It came from students in a focus group (Marrone et al., 2024, p. 1862). And they’re not alone in their anxiety. As someone who teaches academic writing to students preparing for university, I hear variations of this fear constantly. But here’s what I tell them. The question isn’t whether AI will impact your future. The question is whether you’ll be ready.

The Reality Check: What the Data Actually Says

Let’s look at the numbers. According to the World Economic Forum (2025), AI and information-processing technologies will create 11 million jobs but displace 9 million. The pattern is clear. AI will create high-skill, high-wage technical roles while eliminating routine clerical and administrative tasks.But here’s what caught my attention: analytical thinking remains the most sought-after skill, with seven out of 10 companies considering it essential in 2025. Not AI tool mastery. Not prompt engineering. Analytical thinking.This matters because some skills taught today might become obsolete by the time students who started university in September 2025 graduate in 2030. Yet the ability to think critically, evaluate information, and create original work will remain invaluable, especially in an AI-saturated world.

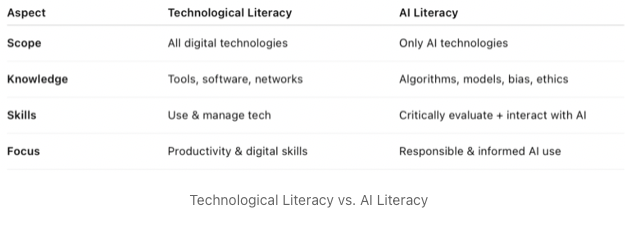

The Confusion: Technology Literacy vs. AI Literacy

Here’s where things get messy.

As I scroll through educational blogs and social media, I see “AI literacy” used to describe almost anything involving technology in the classroom: using ChatGPT to brainstorm ideas, having students try out AI tools, or automating tasks. But this isn’t AI literacy. It’s technology literacy with a trendy label.

Let me clarify the distinction:

Technology Literacy (OECD, 2019a):“The ability to use, manage, understand and assess technology.”

AI Literacy (Council of Europe, 2024):“The competences, knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that individuals need to understand AI and its impact on their lives, to use AI systems effectively and safely, and to critically assess and engage with AI-driven environments.”

As I scroll through educational blogs and social media, I see “AI literacy” used to describe almost anything involving technology in the classroom: using ChatGPT to brainstorm ideas, having students try out AI tools, or automating tasks. But this isn’t AI literacy. It’s technology literacy with a trendy label.

Let me clarify the distinction:

Technology Literacy (OECD, 2019a):“The ability to use, manage, understand and assess technology.”

AI Literacy (Council of Europe, 2024):“The competences, knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that individuals need to understand AI and its impact on their lives, to use AI systems effectively and safely, and to critically assess and engage with AI-driven environments.”

See the difference? One is about operating tools. The other is about understanding, evaluating, and engaging critically with an entirely new form of technology that claims to “think.”

The Core Problem: AI Isn’t Actually Intelligent

This brings us to the elephant in the room. Artificial Intelligence isn’t really intelligence at all. It is prediction.

The term “Artificial Intelligence” is capitalised because it’s “a specific field of inquiry and development, and not simply a type of intelligence that is artificial” (Holmes & Tuomi, 2022, p. 546). Some experts argue more bluntly. AI cannot be identified as intelligence because what it actually does is make predictions based on patterns (Feingold, 2023).

Why does this matter for students? Because true intelligence requires something AI doesn’t have: consciousness.

According to Piaget (1952; 1970), intelligence is not simply a fixed capacity, but a dynamic process of adaptation that becomes most evident in novel situations. It involves consciously reflecting on one’s actions and reorganising them through mental operations, enabling individuals to construct new understanding when prior knowledge is insufficient.

AI can’t do any of this. It can’t reflect. It can’t truly understand. It can’t make meaning. It predicts the next word, the next image, the next pattern but it doesn’t know anything.

And this is precisely why our students need AI literacy: to understand the difference between prediction and intelligence, between pattern-matching and genuine thought.

The term “Artificial Intelligence” is capitalised because it’s “a specific field of inquiry and development, and not simply a type of intelligence that is artificial” (Holmes & Tuomi, 2022, p. 546). Some experts argue more bluntly. AI cannot be identified as intelligence because what it actually does is make predictions based on patterns (Feingold, 2023).

Why does this matter for students? Because true intelligence requires something AI doesn’t have: consciousness.

According to Piaget (1952; 1970), intelligence is not simply a fixed capacity, but a dynamic process of adaptation that becomes most evident in novel situations. It involves consciously reflecting on one’s actions and reorganising them through mental operations, enabling individuals to construct new understanding when prior knowledge is insufficient.

AI can’t do any of this. It can’t reflect. It can’t truly understand. It can’t make meaning. It predicts the next word, the next image, the next pattern but it doesn’t know anything.

And this is precisely why our students need AI literacy: to understand the difference between prediction and intelligence, between pattern-matching and genuine thought.

Why This Matters for Academic Writing

Many educators worry that students will use AI to cheat or bypass learning. I’ve taken a different approach. Instead of fighting AI or ignoring it, I’ve integrated AI literacy directly into academic essay writing instruction for 18+ students preparing for university.

Here’s why. Academic writing is the perfect vehicle for teaching AI literacy because it requires exactly what AI cannot do—critical thinking, original synthesis, and meaningful analysis.

Here’s why. Academic writing is the perfect vehicle for teaching AI literacy because it requires exactly what AI cannot do—critical thinking, original synthesis, and meaningful analysis.

My Framework: AI Literacy Through Academic Writing

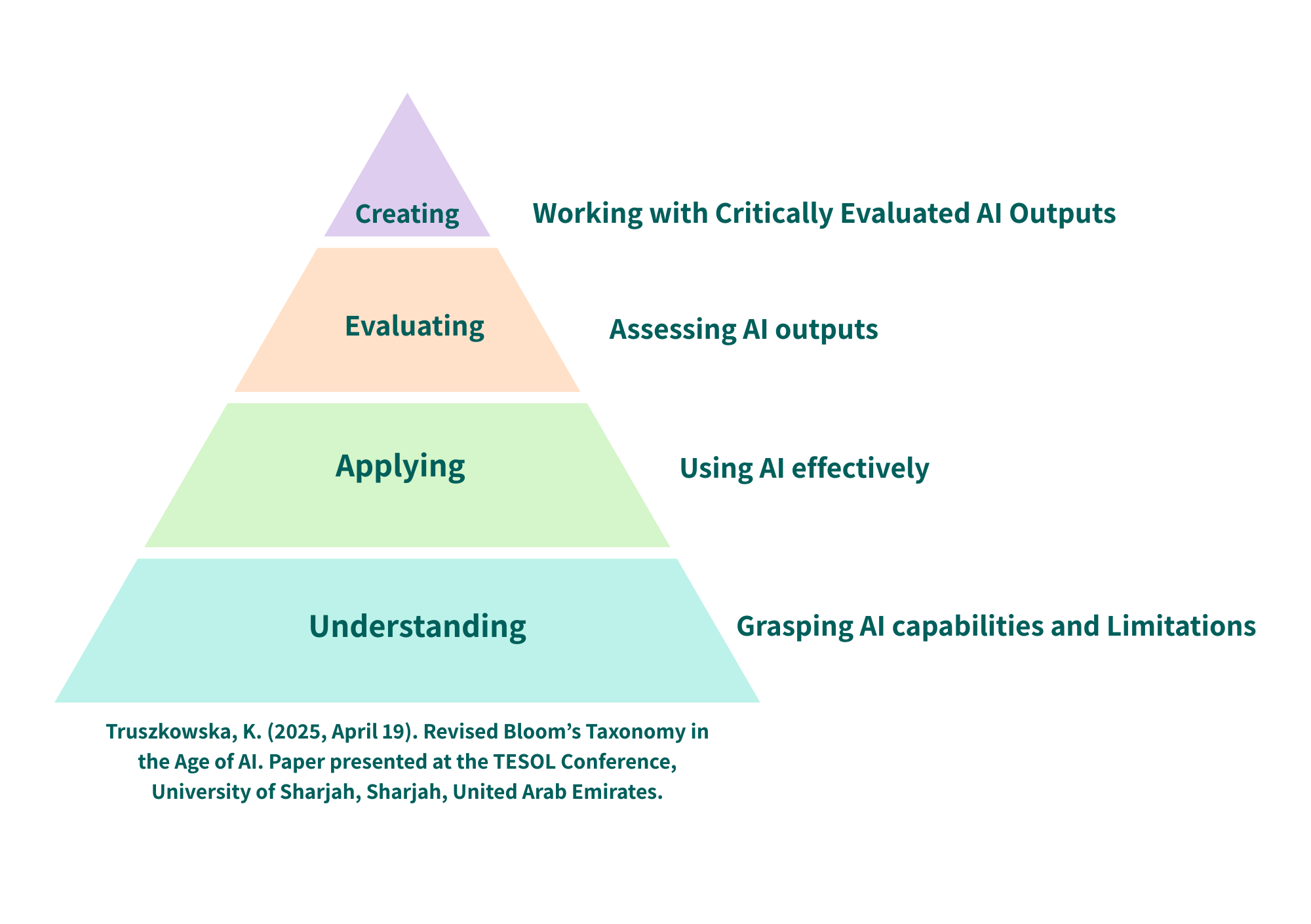

At the TESOL Conference at the University of Sharjah this year, I presented a framework grounded in Bloom’s Taxonomy that integrates AI literacy into essay writing instruction. It works in four progressive stages.

1. Understand: Learn AI’s Capabilities and Limitations

Students explore what AI can and cannot do. They discover that AI can generate text but cannot evaluate sources, cannot determine what’s academically credible, and cannot create original arguments. This builds realistic expectations.

2. Apply: Use AI Tools Responsibly and Appropriately

Students learn when and how to use AI ethically, e.g. for brainstorming, for understanding complex concepts, for refining grammar, but never as a substitute for their own thinking. They practice transparent documentation of AI use.

3. Evaluate: Critically Assess AI’s Output

This is where the magic happens. Students fact-check AI-generated content, identify hallucinations, spot logical fallacies, and recognise when AI produces plausible-sounding nonsense. They become AI’s evaluators, not its consumers.

4. Create: Co-create Original Work with AI as Support

Finally, students produce genuinely original academic essays where AI serves as a tool—like a sophisticated thesaurus or research assistant—but where their critical thinking, their analysis, and their voice remain central.

The Result: Students Who Can Actually Think

This isn’t just theoretical. When students work through this framework, something shifts. They stop seeing AI as either a magical solution or a terrifying threat. Instead, they see it for what it is: a powerful tool that can support but never replace human intelligence.

The Bottom Line

The future belongs to students who can do what AI cannot: think critically, evaluate information, synthesise original ideas, and reflect consciously on their work.

AI literacy isn’t about learning to use ChatGPT. It’s about understanding the fundamental difference between prediction and intelligence and developing the skills that will remain uniquely human, no matter how sophisticated the algorithms become.

For 18+ students preparing for university, mastering academic writing with this AI-literate approach isn’t just preparation for their essays. It’s preparation for a working world where analytical thinking, not tool mastery, will be the skill that matters most.

The question isn’t whether your students will encounter AI. The question is whether they’ll be ready to think for themselves when they do.

AI literacy isn’t about learning to use ChatGPT. It’s about understanding the fundamental difference between prediction and intelligence and developing the skills that will remain uniquely human, no matter how sophisticated the algorithms become.

For 18+ students preparing for university, mastering academic writing with this AI-literate approach isn’t just preparation for their essays. It’s preparation for a working world where analytical thinking, not tool mastery, will be the skill that matters most.

The question isn’t whether your students will encounter AI. The question is whether they’ll be ready to think for themselves when they do.

References:

Council of Europe. (2024). Recommendation CM/Rec(2024)3 of the Committee of Ministers to member States on artificial intelligence literacy. Council of Europe.

Feingold, S. (2023, March 8). What is artificial intelligence—and what is it not? World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/03/what-is-artificial-intelligence-and-what-is-it-not-ai-machine-learning/

Holmes, W. (2024). AIED—Coming of age? International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 34(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-023-00352-3

Holmes, W., & Tuomi, I. (2022). State of the art and practice in AI in education. European Journal of Education, 57(3), 542–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12533

Marrone, R., Zamecnik, A., Joksimovic, S., Johnson, J., & De Laat, M. (2024). Understanding student perceptions of artificial intelligence as a teammate. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 30, 1847-1869. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-024-09780-z

Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children (M. Cook, Trans.). International Universities Press. (Original work published 1936)

Piaget, J. (1970). Genetic epistemology (E. Duckworth, Trans.). Columbia University Press.

OECD. (2013).OECD skills outlook 2013: First results from the survey of adult skills. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019a). The future of education and skills: Education 2030—OECD learning compass 2030. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019b).OECD principles on artificial intelligence. OECD Publishing.UNESCO. (2018). ICT competency framework for teachers (Version 3).

UNESCO.World Economic Forum. (2025). Future of jobs report 2025. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2025/

Feingold, S. (2023, March 8). What is artificial intelligence—and what is it not? World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/03/what-is-artificial-intelligence-and-what-is-it-not-ai-machine-learning/

Holmes, W. (2024). AIED—Coming of age? International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 34(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-023-00352-3

Holmes, W., & Tuomi, I. (2022). State of the art and practice in AI in education. European Journal of Education, 57(3), 542–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12533

Marrone, R., Zamecnik, A., Joksimovic, S., Johnson, J., & De Laat, M. (2024). Understanding student perceptions of artificial intelligence as a teammate. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 30, 1847-1869. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-024-09780-z

Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children (M. Cook, Trans.). International Universities Press. (Original work published 1936)

Piaget, J. (1970). Genetic epistemology (E. Duckworth, Trans.). Columbia University Press.

OECD. (2013).OECD skills outlook 2013: First results from the survey of adult skills. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019a). The future of education and skills: Education 2030—OECD learning compass 2030. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019b).OECD principles on artificial intelligence. OECD Publishing.UNESCO. (2018). ICT competency framework for teachers (Version 3).

UNESCO.World Economic Forum. (2025). Future of jobs report 2025. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2025/

Get in touch

-

Oxford Academy Of English Ltd

-

The Wheelhouse Angel Court, 81 St Clements, Oxford, OX4 1AW, UK

-

contact@oaoe.co.uk

-

+44 (0) 7356 030202

Our Newsletter

Get weekly updates on live streams, news, tips & tricks and more.

Thank you!

Copyright © 2025